PSL/A Practical Introduction to PSL/Basic Temporal Properties/ru

- Introduction (en)

- Basic Temporal Properties (en)

- Some Philosophy (en)

- Weak vs. Strong Temporal Operators (en)

Содержание |

Основные временные свойства While

В то время как Булевый слой состоит из Булевых выражений, которые выполняются или не выполняются в данном цикле, временной слой предоставляет путь для описания взаимоотношений между Булевыми выражениями по времени. PSL утверждение обычно представлено только в одном направлении - вперед, от первого цикла (также можно двигаться в обратном направлении, используя встроенные функции, такие как prev(), rose() и fell()). Таким образом, простое PSL утверждение assert a; показывает, что a должно утверждаться в самом первом цикле, в то время как PSL утверждение assert always a, показывает, что a должно утверждаться в перовм цикле и в каждом следующем цикле, а это значит, что в каждом цикле.

Комбинированием временных операторов различными путями, мы можем установить свойства, такие как “каждый запрос получает подтверждение”, “каждому подтвержденному запросу предоставляется от четырех до семи циклов, в случаи, если запрос не приостановится первым”, “две последовательные записи не должны располагать по одному и тому же адресу” и “когда мы видим запрос на чтение с тэгом i, на следующих четырех передах данных ожидается увидеть тэг i”.

Временной слой состоит из фундаментального языка (FL) и дополнительного расширения ветвления (OBE). FL используется для выражения свойств одного тракта, а также используется для моделирования или формальной верификации. OBE используется для выражения свойств, относящихся к набору трактов, например, “существует тракт, такой как ...”, и также используется для формальной верификации. В этой книге мы сконцентрируемся на фундаментальном языке.

Фундаментальный язык состоит из двух комплементарных стилей - LTL стиль, названный из-за временной логики LTL, на которой базируется PSL, и SERE стиля, названного из-за последовательного расширения регулярных выражений PSL, или SEREs. В этой главе мы представим основные временные операторы LTL стиля. Мы предоставим то, что будет достаточно для понимания основной идеи, и чтобы дать некий контекст, для философских замечаний,обсуждаемых далее.

В этой книге, мы широко используем примеры. Каждый пример свойства или утверждения связан с временной диаграммой (которую мы называем тракт) сгруппирован вместе на рисунке. Такой рисунок будет содержать один или более трактов, нумерованных в скобках строчными римскими цифрами, одного или более свойств, нумерованных добавление строчной буквы к номеру рисунка. Например, Рисунок 2.1 содержит тракт 2.1(i) и утверждения 2.1а, 2.1b, 2.1c.

2.1 Операторы always и never

Нам уже встречались основные временные операторы always и never. Большинство свойств PSL начинаются с одного или с другого. Это, потому что “голое” (Булево) PSL свойство относится только к первому циклу тракта. Например, утверждение 2.1a требует только того, чтобы Булево выражение !(a && b) выполнялось в первом цикле. Таким образом, утверждение 2.1а выполняется в тракте 2.1(i), потому что Булево выражение !(a && b) выполняется в цикле 0. Для того, чтобы сформулировать, что мы хотим, чтобы оно выполнялось в каждом цикле проекта, мы должны добавить временной оператор always, и получить утверждение 2.1b. Утверждение 2.1b не поддерживает тракт 2.1(i), потому что Булево выражение !(a && b) не выполняется в цикле 5. Эквивалентно, мы можем поменять оператор always и Булево отрицание ! с never, чтобы получить утверждение 2.1с.

|

|---|

| (i) Утверждение 2.1a выполняется, но 2.1b and 2.1c нет |

assert !(a && b); (2.1a) assert always !(a && b); (2.1b) assert never (a && b); (2.1c) |

| Рис. 2.1: Операторы always и never |

Оба утверждения 2.1b и 2.1c показывают, что сигналы a и b взаимоисключающиеся. Очевидно, все, что может использоваться с оператором always, может также использоваться с оператором never и наоборот, происходит простое отрицанием операнда, когда происходит переключение между always и never. PSL, для удобства, предоставляет два варианта использования, иногда более удобно описать свойство положительным (если свойство выполняется на всех циклах), а иногда удобней отрицательным (если свойство не выполняется ни в каком цикле). В общем, существует много путей описания свойств в PSL. Мы рассмотрим другие примеры далее.

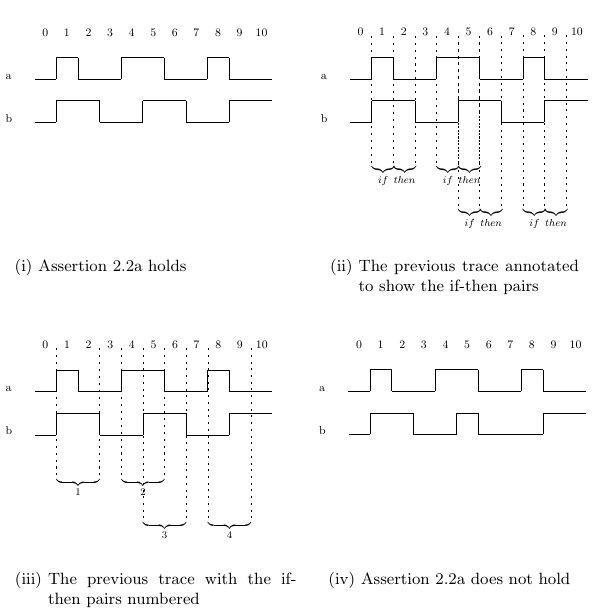

2.2 Оператор next

Другой временной оператор - это оператор next. Он показывает, что свойство свойство должно выполняться, если его операнд выполняется в следующем цикле. Например, утверждение 2.2a показывает, что когда бы a не выполнялось, b должно выполниться в следующем цикле. Утверждение 2.2a использует другой важный оператор, логический оператор импликации (->). В то время как оператор логической импликации Булевый, а не временной (он не свяжет два подсвойства по времени), это играет очень важную роль во многих временных свойствах. Логическая импликация prop1 -> prop2 выполняется, если prop1 не выполняется или prop2 выполняется. Это хорошо представляется, если принять это, как выражение вида if-then, с частью else. prop1 -> prop2 можно понимать, как если prop1, то далее следует prop2, иначе возвращается значение правда. Таким образом, под-свойство a -> next b, в нашем примере, выполняется, если a не выполняется (потому что свойство по умолчание имеет значение правда) или, если a выполняется, а также и next b выполняется. Добавляя оператор always, мы получаем свойство, которое выполняется, если под-свойство a -> next b выполняется в каждом цикле. Таким образом, утверждение 2.2а показывает, что когда бы ни выполнялось a, b должно выполняться в следующем цикле. Утверждение 2.2а выполняется по сигналу b. Это показано в “if” и “then” примечании на тракте 2.2(ii). “Дополнительные” утверждения сигнала b на циклах 1 и 10, спровоцированы утверждение 2.2а, потому что в нем ничего не сказано о значениях b в цикле, кроме того, что следует из из утверждения a.

Отметим, что циклы вовлеченные в выполнение одного утверждения сигнала, могут перекрываться с теми,которые вовлечены в выполнение другого утверждения. Например, учитывая тракт 2.2(iii), который является простым трактом 2.2(ii) с if-then пронумерованными парами. Имеем четыре утверждения сигнала a на тракте 2.2(iii), и таким образом четыре связанных цикла, в которых b должен утверждаться. Каждая пара циклов (утверждение a следует из утверждения b) нумерованы в тракте 2.2(iii). Рассматривая пары 2 и 3. Сигнал a утверждается в 4 цикле пары 2, таким образом сигнал b должен утвердиться в 5 цикле, для того, чтобы утверждение 2.2а выполнялось. Сигнал а утверждается в цикле 5 пары 3, таким образом требуется утверждение сигнала b в 6 цикле. Пары 2 и 3 перекрываются, потому что, в то время как мы ищем утверждение сигнала b в 5 цикле, для выполнения утверждения a в 4 цикле, также, мы видим дополнительное утверждение сигнала a, который рассматривается.

Утверждение 2.2а не выполняется в тракте 2.2(iv), потому что третье утверждение сигнала a, в цикле 5, т.к. отсутствует утверждение сигнала b в следующем цикле.

|

|---|

assert always (a -> next b); (2.2a) |

| Рис.2.2: Операторы next и логическая импликация |

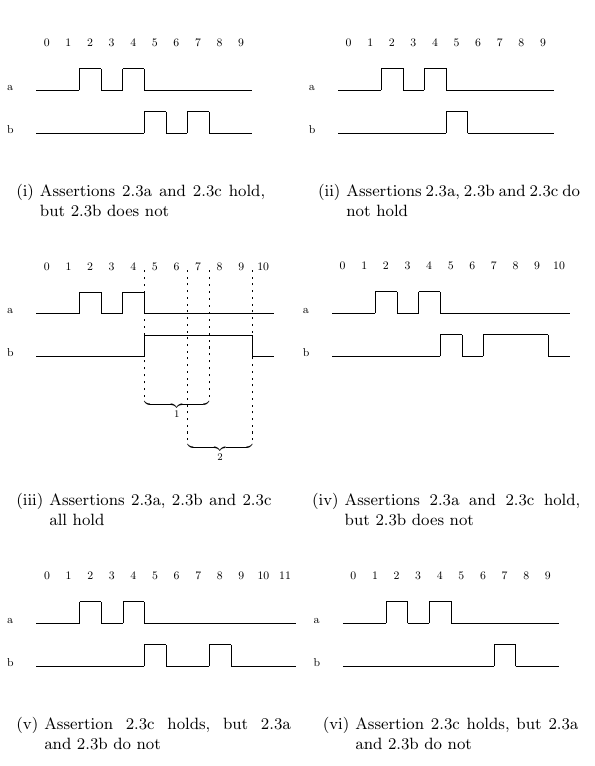

2.3 вариации next, включая next_event

Свойство next выполняется, если его операнд выполняется в следующем цикле. Вариации оператора next позволяют указывать n-й следующий цикл и диапазоны будущих циклов. Свойство next[n] выполняется, если его операнд выполняется в n-й следующий цикл. Например, утверждение 2.3а показывает, что когда бы сигнал a не выполнялся, сигнал b выполниться тремя циклами позже. Утверждение 2.3а выполняется в тактах 2.3(i), 2.3(iii), 2.3(iv), но не выполняется в трактах 2.3(ii) или 2.3(v), потому что отсутствует утверждение сигнала b в цикле 7, и не выполняется в тракте 2.3(vi), потому что отсутствует утверждение сигнала b в цикле 5.

|

|---|

assert always (a -> next[3] (b)); (2.3a) assert always (a -> next_a[3:5] (b)); (2.3b) assert always (a -> next_e[3:5] (b)); (2.3c) |

Рис. 2.3: Операторы next[n], next_a[i:j] и next_e[i:j]

|

Свойство next_a[i:j] выполняется если его операнд выполняется во всех циклах от i-го следующего, до j-го следующего цикла включительно. Например, утверждение 2.3b показывает, что когда бы сигнал a не выполнялся, сигнал b выполняется тремя, четырьмя, пятью циклами позже. Выполняется в тракте 2.3(iii) и не выполняется в трактах 2.3(i), 2.3(ii), 2.3(iv), 2.3(v) или 2.3(vi).

Ранее мы обсуждали то факт, что циклы, вовлеченные в выполнение одного утверждения сигнала, могут перекрываться с циклами, вовлеченными для выполнения других утверждений сигнала. Тракт 2.3(iii) был представлен, чтобы с акцентировать это для утверждения 2.3b. Сигнал b должен утверждаться в циклах с 5 до 7 (помечено “1”), в связи с утверждением сигнала a в цикле 2, и должен утверждаться в циклах с 7 до 9 (помечено “2”), в связи с утверждением в цикле 4.

Свойство next_e[i:j] выполняется, если существует цикл со следующего i до следующих j циклов, в которых выполняются операнды. Например, утверждение 2.3с показывает, что когда бы сигнал a не выполнялся, сигнал b выполняется тремя, четырьмя или пятью циклами позже. Нету ничего в утверждении 2.3с, что предотвращает единичное утверждение сигнала b из выполнения многочисленных утверждений сигнала a, таким образом это выполняется в тракте 2.3(vi), потому что утверждение сигнала b, в цикле 7, появляется через 5 циклов после утверждения сигнала a в цикле 2, и через три цикла после утверждения сигнала a в цикле 4.

Assertion 2.3c also holds on Traces 2.3(i), 2.3(iii), 2.3(iv), and 2.3(v),

since there are enough assertions of signal b at the appropriate times. In

Traces 2.3(i), 2.3(iii), and 2.3(iv) there are more than enough assertions of b

to satisfy the property being asserted (in Trace 2.3(i), the assertion of b at

cycle 7 is enough, because it comes five cycles after the assertion of a at cycle

2, and three cycles after the assertion of a at cycle 4). In Trace 2.3(v) there

are just enough assertions of b to satisfy the requirements of Assertion 2.3c.

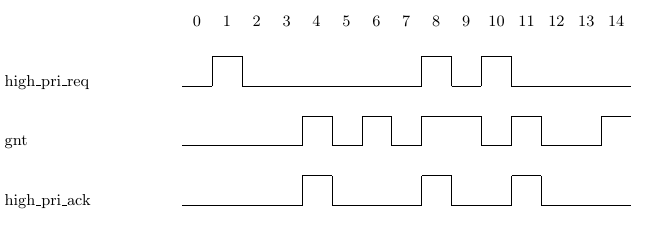

The next_event operator is a conceptual extension of the next operator.

While next refers to the next cycle, next_event refers to the next

cycle in which some Boolean condition holds. For example, Assertion 2.4a

expresses the requirement that whenever a high priority request is received

(signal high_pri_req is asserted), then the next grant (assertion of signal

gnt) must be to a high priority requester (signal high_pri_ack is asserted).

Assertion 2.4a holds on Trace 2.4(i). There are two assertions of signal

high_pri_req, the first at cycle 1 and the second at cycle 10. The associated

assertions of gnt occur at cycles 4 and 11, respectively, and high_pri_ack

holds in these cycles.

The next_event operator includes the current cycle. That is, an assertion

of b in the current cycle will be considered the next assertion of b in the

property next_event(b)(p). For instance, consider Trace 2.4(ii). Trace 2.4(ii)

is similar to Trace 2.4(i) except that there is an additional assertion of

high_pri_req at cycle 8 and two additional assertions of gnt at cycles 8

and 9, one of which has an associated high_pri_ack. Assertion 2.4a holds on

Trace 2.4(ii) because the assertion of gnt at cycle 8 is considered the next

assertion of gnt for the assertion of high_pri_req at cycle 8. If you want to

exclude the current cycle, simply insert a next operator in order to move the

current cycle of the next_event operator over by one, as in Assertion 2.4b.

Assertion 2.4b does not hold on Trace 2.4(ii). Because of the insertion of the

next operator, the relevant assertions of gnt have changed from cycles 4, 8

and 11 for Assertion 2.4a to cycles 4, 9 and 11 for Assertion 2.4b, and at cycle

9 there is no assertion of high_pri_ack in Trace 2.4(ii).

Just as we can use next[i] to indicate the ith next cycle, we can use

next_event(b)[i] to indicate the ith occurrence of b. For example, in order

to express the requirement that every time a request is issued (signal req is

asserted), signal_last ready must be asserted on the fourth assertion of signal

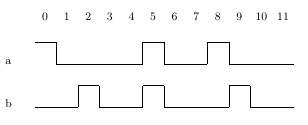

ready, we can code Assertion 2.5a. Assertion 2.5a holds on Trace 2.5(i). For

the first assertion of req, at cycle 1, the four assertions of ready happen

to come immediately and in consecutive cycles. For the second assertion of

req, at cycle 7, the four assertions of ready do not happen immediately and

do not happen consecutively either – they are spread out over seven cycles,

interspersed with cycles in which ready is deasserted. However, the point is

that in both cases, signal last_ready is asserted on the fourth assertion of

ready, thus Assertion 2.5a holds on Trace 2.5(i).

|

|---|

| (i) Assertion 2.5a holds |

assert always (req -> (2.5a) next event(ready)[4](last ready)); |

| Fig. 2.5: next event[n] |

As with next_a[i:j] and next_e[i:j], the next_event operator also

comes in forms that allow it to indicate all of a range of future cycles, or the existence

of a future cycle in such a range. The form next_event_a(b)[i:j](f)

indicates that we expect f to hold on all of the ith through jth occurrences

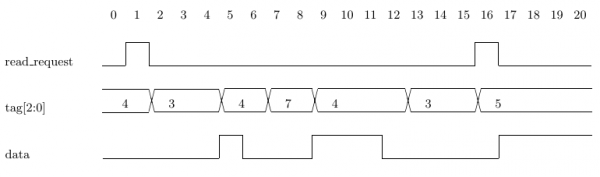

of b. For example, Assertion 2.6a indicates that when we see a read request

(assertion of signal read_request) with tag equal to i, then on the next four

data transfers (assertion of signal data), we expect to see tag i. Assertion 2.6a

uses the forall construct, which we will examine in detail later. For now, suffice

it to say that Assertion 2.6a states a requirement that must hold for all

possible values of the signal tag[2:0]. Assertion 2.6a holds on Trace 2.6(i)

because after the first assertion of signal read_request, where tag[2:0] has

the value 4, the value of tag[2:0] is also 4 on the next four assertions of

signal data (at cycles 5, 9, 10 and 11). Likewise, on the second assertion of

signal read_request, where tag[2:0] has the value 5, the value of tag[2:0]

is also 5 on the next four assertions of signal data (at cycles 17 through 20).

In order to indicate that we expect something to happen on one of the next

ith to jth cycles, we can use the next_event_e(b)[i:j](f) operator, which

indicates that we expect f to hold on one of the ith through jth occurrences of

b. For example, consider again Assertion 2.4a. It requires that whenever a high

priority request is received, the next grant must be to a high priority requester.

Suppose instead that we require that one of the next two grants be to a high

priority requester. We can express this using Assertion 2.7a. Assertion 2.7a

holds on Trace 2.7(i) because every time that signal high_pri_req is asserted,

signal high_pri_ack is asserted on one of the next two assertions of gnt.

The syntax of the range specification for all operators – including those

we have not yet seen – is flavor dependent. In the Verilog, SystemVerilog and

SystemC flavors, it is [i:j]. In the VHDL flavor it is [i to j]. In the GDL

flavor it is [i..j].

|

|---|

| (i) Assertion 2.6a holds |

assert forall i in {0:7}: (2.6a)

always ((read_request && tag[2:0]==i) ->

next_event_a(data)[1:4](tag[2:0]==i));

|

Fig. 2.6 next_event a[i:j]

|

2.4 The until and before operators

|

|---|

| (i) Assertion 2.7a holds |

assert always (high_pri_req -> (2.7a) next_event_e(gnt)[1:2](high_pri_ack)); |

Fig. 2.7: next_event e[i:j]

|

The until operator provides another way to move forward, this time while

putting a requirement on the cycles in which we are moving. For example,

Assertion 2.8a states that whenever signal req is asserted, then, starting at

the next cycle, signal busy must be asserted up until signal done is asserted.

Assertion 2.8a requires that busy will be asserted up to, but not necessarily

including, the cycle where done is asserted. In order to include the cycle where

done is asserted, use the operator until_. The underscore (_) is intended to

represent the extra cycle in which we require that busy should stay asserted,

so Assertion 2.8b states that whenever signal req is asserted, then starting

from the next cycle, busy must be asserted and must stay asserted up until

and including the cycle where done is asserted. For example, Assertion 2.8a

holds on Trace 2.8(i), but Assertion 2.8b does not, because busy is not asserted at cycles 4 and 10. Both Assertions 2.8a and 2.8b hold on Trace 2.8(ii):

Assertion 2.8a does not prohibit the assertion of busy at cycles 4 and 10 – it

just does not require it.

If signal done is asserted the cycle after signal req is asserted, Assertion 2.8a does not require that signal busy be asserted at all, while Assertion 2.8b does. That is, Assertion 2.8a holds on Trace 2.8(iii) – the fact that

done happens immediately after req leaves no cycles on which busy needs to

be asserted. Assertion 2.8b does not hold on Trace 2.8(iii) because of a missing

assertion of busy in the cycle in which done is asserted.

|

|---|

assert always (req -> next (busy until done)); (2.8a) assert always (req -> next(busy until_ done)); (2.8b) |

Fig. 2.8: The until and until_ operators

|

The before family of operators provides an easy way to state that we

require some signal to be asserted before some other signal. For example, suppose that we have a pulsed signal called req, and we have the requirement that

before we can make a second request, the first must be acknowledged. We can

express this in PSL using Assertion 2.9a. We need the next to take us forward

one cycle so that the req in (ack before req) is sure to refer to some other

req, and not the one we have just seen. To understand this, let us examine a

flawed version of the same specification. Consider Assertion 2.9b. It requires

that (ack before req) hold at every cycle in which req holds. Consider,

for example, cycle 1 of Trace 2.9(i). Signal req is asserted. Therefore, (ack before req) must hold at cycle 1. However, it does not, because starting at

cycle 1 and looking forward, we first see an assertion of signal req (at cycle 1),

and only afterwards an assertion of signal ack (at cycle 3) – so req is asserted

before ack, and not the other way around. Assertion 2.9a, on the other hand,

states what we want: at cycle 1, for example, we require next (ack before req) to hold. Therefore, we require that (ack before req) hold at cycle 2.

Starting at cycle 2 and looking forward, we first see an assertion of ack (at

cycle 3), and only afterwards an assertion of req (at cycle 6).

The before operator requires that its first operand happen strictly before

its second. In order to specify that something must happen before or at the

same cycle as something else, use before_. The underscore (_) is intended

to represent the cycle in which we allow an overlap between the left and

right sides. For example, in order to specify that behavior like that shown

in Trace 2.9(i) is allowed, and that in addition behavior like that shown in

Trace 2.9(ii) is allowed, use Assertion 2.9c.

What if the assertion of ack is allowed to come, not together with the next

assertion of req, but rather together with the request being acknowledged?

In other words, what if in addition to the behavior shown in Trace 2.9(i), we

want to allow the behavior shown in Trace 2.9(iii)? As we have seen previously,

Assertion 2.9b is not the answer. Rather, we can code Assertion 2.9d.

2.5 eventually!

The eventually! operator allows you to specify that something must occur in

the future without saying exactly when. For example, Assertion 2.10a states

that every request (assertion of req) must be followed at some time with

an acknowledge (assertion of ack). There is nothing in Assertion 2.10a to

prevent a single acknowledge from satisfying the requirement for multiple

requests, thus Assertion 2.10a holds on Trace 2.10(i). We examine the issue

of specifying a one-to-one correspondence between signals in Section 13.4.2.

The exclamation point (!) of the eventually! operator indicates that it

is a strong operator. We discuss weak vs. strong temporal operators in detail

in Chapter 4.

|

|---|

| (i) Assertion 2.10a holds |

assert always (req -> eventually! ack); (2.10a) |

Fig. 2.10: The eventually! operator

|