PSL/A Practical Introduction to PSL/Basic Temporal Properties/ru

- 1. Introduction (en)

- 2. Basic Temporal Properties (en)

- 3. Some Philosophy (en)

- 4. Weak vs. Strong Temporal Operators (en)

- 5. SERE Style (en)

Содержание |

Основные временные свойства While

В то время как Булевый слой состоит из Булевых выражений, которые выполняются или не выполняются в данном цикле, временной слой предоставляет путь для описания взаимоотношений между Булевыми выражениями по времени. PSL утверждение обычно представлено только в одном направлении - вперед, от первого цикла (также можно двигаться в обратном направлении, используя встроенные функции, такие как prev(), rose() и fell()). Таким образом, простое PSL утверждение assert a; показывает, что a должно утверждаться в самом первом цикле, в то время как PSL утверждение assert always a, показывает, что a должно утверждаться в перовм цикле и в каждом следующем цикле, а это значит, что в каждом цикле.

Комбинированием временных операторов различными путями, мы можем установить свойства, такие как “каждый запрос получает подтверждение”, “каждому подтвержденному запросу предоставляется от четырех до семи циклов, в случаи, если запрос не приостановится первым”, “две последовательные записи не должны располагать по одному и тому же адресу” и “когда мы видим запрос на чтение с тэгом i, на следующих четырех передах данных ожидается увидеть тэг i”.

Временной слой состоит из фундаментального языка (FL) и дополнительного расширения ветвления (OBE). FL используется для выражения свойств одного тракта, а также используется для моделирования или формальной верификации. OBE используется для выражения свойств, относящихся к набору трактов, например, “существует тракт, такой как ...”, и также используется для формальной верификации. В этой книге мы сконцентрируемся на фундаментальном языке.

Фундаментальный язык состоит из двух комплементарных стилей - LTL стиль, названный из-за временной логики LTL, на которой базируется PSL, и SERE стиля, названного из-за последовательного расширения регулярных выражений PSL, или SEREs. В этой главе мы представим основные временные операторы LTL стиля. Мы предоставим то, что будет достаточно для понимания основной идеи, и чтобы дать некий контекст, для философских замечаний,обсуждаемых далее.

В этой книге, мы широко используем примеры. Каждый пример свойства или утверждения связан с временной диаграммой (которую мы называем тракт) сгруппирован вместе на рисунке. Такой рисунок будет содержать один или более трактов, нумерованных в скобках строчными римскими цифрами, одного или более свойств, нумерованных добавление строчной буквы к номеру рисунка. Например, Рисунок 2.1 содержит тракт 2.1(i) и утверждения 2.1а, 2.1b, 2.1c.

2.1 Операторы always и never

Нам уже встречались основные временные операторы always и never. Большинство свойств PSL начинаются с одного или с другого. Это, потому что “голое” (Булево) PSL свойство относится только к первому циклу тракта. Например, утверждение 2.1a требует только того, чтобы Булево выражение !(a && b) выполнялось в первом цикле. Таким образом, утверждение 2.1а выполняется в тракте 2.1(i), потому что Булево выражение !(a && b) выполняется в цикле 0. Для того, чтобы сформулировать, что мы хотим, чтобы оно выполнялось в каждом цикле проекта, мы должны добавить временной оператор always, и получить утверждение 2.1b. Утверждение 2.1b не поддерживает тракт 2.1(i), потому что Булево выражение !(a && b) не выполняется в цикле 5. Эквивалентно, мы можем поменять оператор always и Булево отрицание ! с never, чтобы получить утверждение 2.1с.

|

|---|

| (i) Утверждение 2.1a выполняется, но 2.1b and 2.1c нет |

assert !(a && b); (2.1a) assert always !(a && b); (2.1b) assert never (a && b); (2.1c) |

| Рис. 2.1: Операторы always и never |

Оба утверждения 2.1b и 2.1c показывают, что сигналы a и b взаимоисключающиеся. Очевидно, все, что может использоваться с оператором always, может также использоваться с оператором never/code> и наоборот, происходит простое отрицанием операнда, когда происходит переключение между <code>always и never. PSL, для удобства, предоставляет два варианта использования, иногда более удобно описать свойство положительным (если свойство выполняется на всех циклах), а иногда удобней отрицательным (если свойство не выполняется ни в каком цикле). В общем, существует много путей описания свойств в PSL. Мы рассмотрим другие примеры далее.

2.2 Оператор next

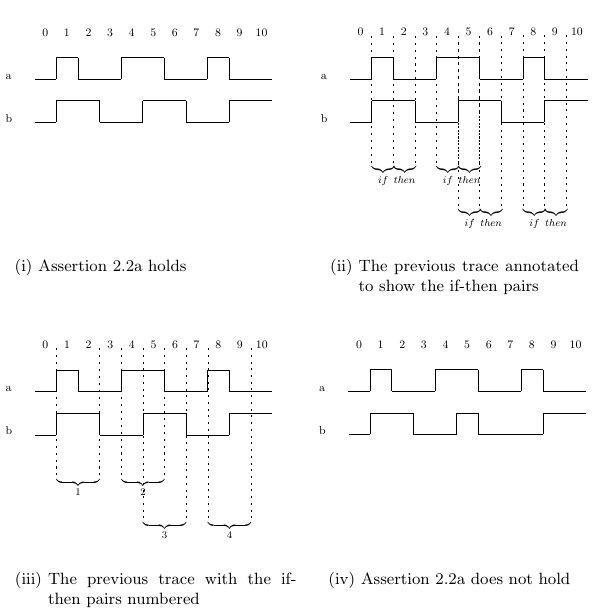

Другой временной оператор - это оператор next. Он показывает, что свойство свойство должно выполняться, если его операнд выполняется в следующем цикле. Например, утверждение 2.2a показывает, что когда бы a не выполнялось, b должно выполниться в следующем цикле. Утверждение 2.2a использует другой важный оператор, логический оператор импликации (->). В то время как оператор логической импликации Булевый, а не временной (он не свяжет два подсвойства по времени), это играет очень важную роль во многих временных свойствах.

Note that the cycles involved in satisfying one assertion of signal a may

overlap with those involved in satisfying another assertion. For example, consider

Trace 2.2(iii), which is simply Trace 2.2(ii) with the if-then pairs numbered.

There are four assertions of signal a on Trace 2.2(iii), and thus four

associated cycles in which b must be asserted. Each pair of cycles (an assertion

of a followed by an assertion of b) is numbered in Trace 2.2(iii). Consider

pairs 2 and 3. Signal a is asserted at cycle 4 in pair 2, thus signal b needs to

be asserted at cycle 5 in order for Assertion 2.2a to hold. Signal a is asserted

at cycle 5 in pair 3, thus requiring that signal b be asserted at cycle 6. Pairs

2 and 3 overlap, because while we are looking for an assertion of signal b at

cycle 5 in order to satisfy the assertion of a at cycle 4, we see an additional

assertion of signal a that must be considered.

Assertion 2.2a does not hold on Trace 2.2(iv) because the third assertion

of signal a, at cycle 5, is missing an assertion of signal b at the following cycle.

|

|---|

assert always (a -> next b); (2.2a) |

| Fig. 2.2: The next and logical implication operators |

2.3 Variations on next including next_event

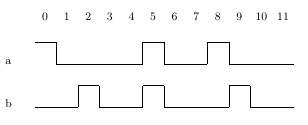

A next property holds if its operand holds in the next cycle. Variations on the

next operator allow you to specify the nth next cycle, and ranges of future

cycles. A next[n] property holds if its operand holds in the nth next cycle.

For example, Assertion 2.3a states that whenever signal a holds, signal b holds

three cycles later. Assertion 2.3a holds on Traces 2.3(i), 2.3(iii), and 2.3(iv),

while it does not hold on Traces 2.3(ii) or 2.3(v) because of a missing assertion

of signal b at cycle 7, and does not hold on Trace 2.3(vi) because of a missing

assertion of signal b at cycle 5.

|

|---|

assert always (a -> next[3] (b)); (2.3a) assert always (a -> next_a[3:5] (b)); (2.3b) assert always (a -> next_e[3:5] (b)); (2.3c) |

Fig. 2.3: Операторы next[n], next_a[i:j] и next_e[i:j]

|

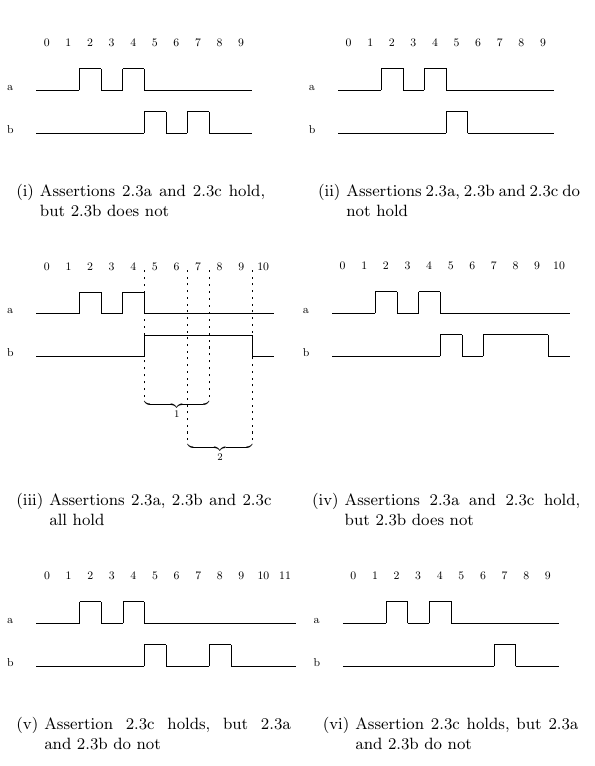

A next_a[i:j] property holds if its operand holds in all of the cycles from

the ith next cycle through the jth next cycle, inclusive. For example, Assertion

2.3b states that whenever signal a holds, signal b holds three, four and

five cycles later. It holds on Trace 2.3(iii) and does not hold on Traces 2.3(i),

2.3(ii), 2.3(iv), 2.3(v), or 2.3(vi).

Previously we discussed the fact that the cycles involved in satisfying one

assertion of signal a may overlap those involved in satisfying another assertion

of a. Trace 2.3(iii) has been annotated to emphasize this point for Assertion

2.3b. Signal b must be asserted in cycles 5 through 7 (marked as “1”)

because of the assertion of a at cycle 2, and must be asserted in cycles 7

through 9 (marked as “2”) because of the assertion of a at cycle 4.

A next_e[i:j] property holds if there exists a cycle from the next i

through the next j cycles in which its operand holds. For example, Assertion

2.3c states that whenever signal a holds, signal b holds either three, four,

or five cycles later. There is nothing in Assertion 2.3c that prevents a single

assertion of signal b from satisfying multiple assertions of signal a, thus it

holds on Trace 2.3(vi) because the assertion of b at cycle 7 comes five cycles

after the assertion of signal a at cycle 2, and three cycles after the assertion

of signal a at cycle 4. We examine the issue of specifying a one-to-one

correspondence between signals in Section 13.4.2.

Assertion 2.3c also holds on Traces 2.3(i), 2.3(iii), 2.3(iv), and 2.3(v),

since there are enough assertions of signal b at the appropriate times. In

Traces 2.3(i), 2.3(iii), and 2.3(iv) there are more than enough assertions of b

to satisfy the property being asserted (in Trace 2.3(i), the assertion of b at

cycle 7 is enough, because it comes five cycles after the assertion of a at cycle

2, and three cycles after the assertion of a at cycle 4). In Trace 2.3(v) there

are just enough assertions of b to satisfy the requirements of Assertion 2.3c.

The next_event operator is a conceptual extension of the next operator.

While next refers to the next cycle, next_event refers to the next

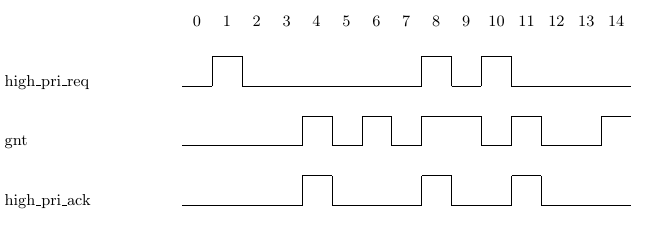

cycle in which some Boolean condition holds. For example, Assertion 2.4a

expresses the requirement that whenever a high priority request is received

(signal high_pri_req is asserted), then the next grant (assertion of signal

gnt) must be to a high priority requester (signal high_pri_ack is asserted).

Assertion 2.4a holds on Trace 2.4(i). There are two assertions of signal

high_pri_req, the first at cycle 1 and the second at cycle 10. The associated

assertions of gnt occur at cycles 4 and 11, respectively, and high_pri_ack

holds in these cycles.

The next_event operator includes the current cycle. That is, an assertion

of b in the current cycle will be considered the next assertion of b in the

property next_event(b)(p). For instance, consider Trace 2.4(ii). Trace 2.4(ii)

is similar to Trace 2.4(i) except that there is an additional assertion of

high_pri_req at cycle 8 and two additional assertions of gnt at cycles 8

and 9, one of which has an associated high_pri_ack. Assertion 2.4a holds on

Trace 2.4(ii) because the assertion of gnt at cycle 8 is considered the next

assertion of gnt for the assertion of high_pri_req at cycle 8. If you want to

exclude the current cycle, simply insert a next operator in order to move the

current cycle of the next_event operator over by one, as in Assertion 2.4b.

Assertion 2.4b does not hold on Trace 2.4(ii). Because of the insertion of the

next operator, the relevant assertions of gnt have changed from cycles 4, 8

and 11 for Assertion 2.4a to cycles 4, 9 and 11 for Assertion 2.4b, and at cycle

9 there is no assertion of high_pri_ack in Trace 2.4(ii).

Just as we can use next[i] to indicate the ith next cycle, we can use

next_event(b)[i] to indicate the ith occurrence of b. For example, in order

to express the requirement that every time a request is issued (signal req is

asserted), signal_last ready must be asserted on the fourth assertion of signal

ready, we can code Assertion 2.5a. Assertion 2.5a holds on Trace 2.5(i). For

the first assertion of req, at cycle 1, the four assertions of ready happen

to come immediately and in consecutive cycles. For the second assertion of

req, at cycle 7, the four assertions of ready do not happen immediately and

do not happen consecutively either – they are spread out over seven cycles,

interspersed with cycles in which ready is deasserted. However, the point is

that in both cases, signal last_ready is asserted on the fourth assertion of

ready, thus Assertion 2.5a holds on Trace 2.5(i).

|

|---|

| (i) Assertion 2.5a holds |

assert always (req -> (2.5a) next event(ready)[4](last ready)); |

| Fig. 2.5: next event[n] |

As with next_a[i:j] and next_e[i:j], the next_event operator also

comes in forms that allow it to indicate all of a range of future cycles, or the existence

of a future cycle in such a range. The form next_event_a(b)[i:j](f)

indicates that we expect f to hold on all of the ith through jth occurrences

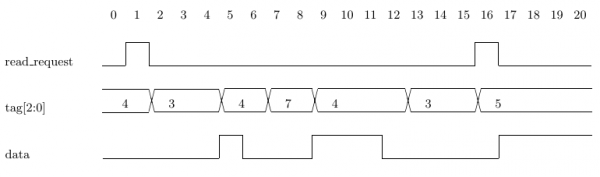

of b. For example, Assertion 2.6a indicates that when we see a read request

(assertion of signal read_request) with tag equal to i, then on the next four

data transfers (assertion of signal data), we expect to see tag i. Assertion 2.6a

uses the forall construct, which we will examine in detail later. For now, suffice

it to say that Assertion 2.6a states a requirement that must hold for all

possible values of the signal tag[2:0]. Assertion 2.6a holds on Trace 2.6(i)

because after the first assertion of signal read_request, where tag[2:0] has

the value 4, the value of tag[2:0] is also 4 on the next four assertions of

signal data (at cycles 5, 9, 10 and 11). Likewise, on the second assertion of

signal read_request, where tag[2:0] has the value 5, the value of tag[2:0]

is also 5 on the next four assertions of signal data (at cycles 17 through 20).

In order to indicate that we expect something to happen on one of the next

ith to jth cycles, we can use the next_event_e(b)[i:j](f) operator, which

indicates that we expect f to hold on one of the ith through jth occurrences of

b. For example, consider again Assertion 2.4a. It requires that whenever a high

priority request is received, the next grant must be to a high priority requester.

Suppose instead that we require that one of the next two grants be to a high

priority requester. We can express this using Assertion 2.7a. Assertion 2.7a

holds on Trace 2.7(i) because every time that signal high_pri_req is asserted,

signal high_pri_ack is asserted on one of the next two assertions of gnt.

The syntax of the range specification for all operators – including those

we have not yet seen – is flavor dependent. In the Verilog, SystemVerilog and

SystemC flavors, it is [i:j]. In the VHDL flavor it is [i to j]. In the GDL

flavor it is [i..j].

|

|---|

| (i) Assertion 2.6a holds |

assert forall i in {0:7}: (2.6a)

always ((read_request && tag[2:0]==i) ->

next_event_a(data)[1:4](tag[2:0]==i));

|

Fig. 2.6 next_event a[i:j]

|